Origins

Kanban, meaning "visual sign" or "card" in Japanese, traces its origins to the 1940s in Toyota's manufacturing system. Taiichi Ohno1 developed it as a tool to control production by signaling demand. Toyota observed how supermarkets managed inventory, stocking just enough product based on customer pull rather than pushing excess onto the shelves. Inspired by this model, Ohno introduced visual signals to regulate production flow, reduce waste, and respond directly to actual demand.

This simple yet powerful signaling method transformed Toyota's production system into a model of just-in-time efficiency, helping establish the foundation for Lean manufacturing principles.

Decades later, David J. Anderson2 recognized that the challenges faced by knowledge workers shared important parallels with the issues Toyota solved. Knowledge work suffers from invisible inventory, bottlenecks, and uneven flow. Anderson adapted the principles of Kanban to software and service work in the early 2000s. He reframed it not as a production technique, but as a method for managing knowledge work through visualization, flow management, work-in-progress limitation, and evolutionary improvement.

Kanban thus emerged not as a rigid methodology, but as a disciplined system to see, understand, and improve work processes.

How Kanban is Used

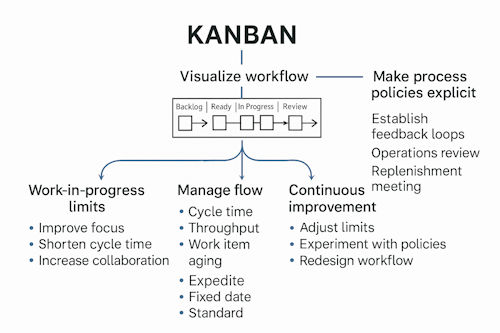

Agile teams adopt Kanban to gain visibility into their workflow and optimize the delivery of value. A Kanban system typically begins with a team mapping their existing process as it truly functions, not how they wish it worked. Columns on a Kanban board represent different states of work, such as "Backlog", "Ready", "In Progress", "Review", and "Done". Items flow across the board from left to right as they progress toward completion.

While work appears to move from left to right, Kanban operates through pull signals that flow from right to left. Each downstream stage requests new work only when ready, pulling items forward based on system capacity. This principle reduces overload and keeps flow stable.

Work-in-progress limits are placed on columns to ensure teams do not start more work than they can effectively handle. When a limit is reached, no new work is pulled in until something is finished. This fosters collaboration, highlights bottlenecks, and maintains a steady pace of delivery.

Organizations extend these practices to the portfolio level. Portfolio Kanban boards represent large initiatives flowing through strategic stages such as discovery, prioritization, delivery, and validation. Because Kanban adapts to existing structures rather than prescribing new ones, it scales naturally across teams, departments, and entire organizations. Linked Kanban systems at different levels create a service-oriented architecture of delivery, with each service optimizing its flow while maintaining alignment with broader organizational goals.

Where Scrum uses time-boxed iterations to control risk and deliver increments, Kanban uses flow control mechanisms to stabilize delivery and optimize responsiveness without the need for iteration planning, Sprint Goals, or formal roles.

Flow Management, WIP Limits, and System Health:

At the heart of Kanban lies the principle of flow management, the continuous, smooth movement of work items from initiation to completion.

Effective flow requires managing work-in-progress carefully. WIP limits are fundamental tools in Kanban, capping the number of items that can exist in a given stage at one time. When WIP is controlled, teams focus their efforts on completing work rather than starting new work, which reduces context switching, accelerates cycle times, and improves quality.

Typical forms of WIP limits include:

- Stage Limits: Maximum number of items allowed in a column, such as "no more than three items in Testing."

- System-wide Limits: Constraints on the total number of active items across all stages.

- Per-Person Limits: Restrictions on the number of active tasks per team member to prevent multitasking overload.

Monitoring flow involves tracking several key metrics:

- Work in Progress (WIP): The number of active work items at any point in time. Tracking WIP helps teams detect overload, identify bottlenecks, and apply Little's Law to forecast delivery.

- Cycle Time: How long it takes for a single item to complete the workflow.

- Throughput: How many items are completed over a given period.

- Work Item Aging: How long individual items have been in progress without completion.

These are often visualized using tools such as:

- Cumulative Flow Diagrams: Graphical views that show the distribution of work over time, helping reveal bottlenecks, flow consistency, and WIP trends.

- Run Charts: Track cycle time or throughput trends over time, helping teams see whether their performance is becoming more stable, improving, or deteriorating.

- Scatter Plots: Visualize the variation in cycle time for individual work items, often used to understand predictability and to spot outliers or anomalies.

- Histograms: Display the frequency distribution of cycle times, showing how consistent the team is in completing work and highlighting clustering or wide variation.

Kanban systems incorporate feedback loops to maintain system health:

- Replenishment meetings occur when input queues run low, prompting teams to prepare the next batch of ready work.

- Daily Flow Reviews allow teams to walk the board together, identifying blocked items, overloaded stages, or deviations from pull rules.

- Operations Reviews analyze systemic performance, identifying improvement opportunities at the team or service level.

These mechanisms create a self-sustaining environment where the team is continually diagnosing and improving the flow of value.

Pull Policies and (Optional) Classes of Service:

A foundational element of Kanban is the use of pull policies, clear agreements about what conditions must be met for work to move between stages. These often include exit criteria that define when an item is ready to leave a stage. Visualizing and enforcing these policies keeps flow reliable and prevents premature handoffs.

Some teams also introduce classes of service to distinguish between different types of work and manage them accordingly:

- Standard Work: Regular features or improvements that flow normally through the system.

- Fixed-Date Work: Items that must be completed by a certain deadline.

- Expedite Work: Critical items that need immediate handling, often overriding other priorities.

- Intangible Work: Important but non-urgent work such as technical debt reduction or exploratory research.

While not required in every Kanban system, these classes help some teams prioritize effectively. Their use depends on the nature of the workflow and organizational context.

When to Use Kanban and When It May Not Fit:

Kanban can be introduced in a wide range of environments, from well-established Agile teams to those just beginning their improvement journey. It is particularly effective when:

- Work is continuous and subject to frequent change.

- Teams value flexibility and real-time prioritization.

- Organizations embrace continuous delivery or Lean startup principles.

- Teams want to evolve their process without major disruptions to roles or structure.

Early challenges may arise when:

- Systems are highly chaotic and lack even basic workflow visibility.

- Organizational mandates require cadence-based planning and synchronized delivery.

- Teams are unfamiliar with self-management and need more structured guidance initially.

Kanban's strength lies in its evolutionary nature, it meets teams where they are and encourages sustainable change through small, data-informed steps. Rather than prescribing roles or events, it provides a framework for learning, adaptation, and system-level improvement.

Key Takeaways

- Kanban is based on visualizing work, limiting WIP, managing flow, and improving incrementally.

- Work-in-progress limits are not optional in serious Kanban systems; they are essential for improving focus and stability.

- Flow-based delivery enables faster value realization, greater predictability, and lower stress on teams.

- Kanban respects existing organizational structures while guiding sustainable change.

- Metrics such as WIP, cycle time, throughput, and aging charts are used to make decisions based on evidence, not assumptions.

- Kanban's success depends on transparency, collective responsibility, and a mindset of continuous learning and improvement.

Summary

Kanban is not merely a visual task board. It is a disciplined system for managing knowledge work through principles of flow, evolutionary change, and system-level thinking. By exposing the true nature of work, controlling overload, and enabling adaptive improvement, Kanban empowers teams to deliver more reliably, sustainably, and thoughtfully.

Where other Agile frameworks offer prescriptions, Kanban offers visibility and choice. It enables teams to learn how their systems behave, to confront constraints honestly, and to evolve based on real data rather than intuition or tradition.

In complex, fast-moving, and unpredictable environments, Kanban provides a structure light enough to bend without breaking, yet strong enough to guide meaningful, lasting change.

Coaching Tips

- Map the Real Workflow: Start with a clear visualization of how work actually flows today. Honesty about the current state is essential for meaningful improvement.

- Use Generous WIP Limits Initially: Set higher WIP limits at the beginning to build psychological safety and trust. Adjust limits downward over time based on real flow observations.

- Focus on Aging Work Daily: Encourage teams to prioritize discussions about aging items rather than just workload. Older work surfaces deeper system problems faster than volume metrics.

- Educate Leaders on Flow Metrics: Teach leadership to view cycle time and throughput as health indicators, not as performance evaluation tools. Metrics should drive improvement, not blame.

- Facilitate System-Level Operations Reviews: Coach teams and leadership to regularly inspect system flow, not just individual team output. Sustainable improvement must happen across services.

- Respect Resistance to Pull Systems: Acknowledge that moving from push to pull challenges entrenched habits. Let teams experiment and adjust at their own pace rather than forcing abrupt change.

- Anchor Team Pride in Flow Success: Celebrate smoother flow, reduced cycle times, and healthier systems as team achievements. De-emphasize checklist completion in favor of real system improvement.